If 2021 was the year that inflation made an unwelcome reappearance and 2022 was when fears of recession stalked financial markets, then 2023 saw share prices (in developed markets, at least) start to discount a much rosier scenario, in the form of a peak in both inflation and interest rates, as well as a soft landing, as the much-discussed downturn failed to materialise.

As a result, technology stocks roared higher (buoyed by AI-oriented narratives), equities had a good year (except in the UK, Hong Kong and China), bonds rallied hard as yields sank in the second half of the year, gold surged, and Bitcoin went bananas.

“It is tempting to argue that 2021-22 was a post-COVID-19 aberration, and that the long-term trend of cheap energy, food, goods and labour that began in the early 1980s has reasserted itself. Markets certainly seen to think so.”

It is tempting to argue that 2021-22 was a post-COVID-19 aberration, and that the long-term trend of cheap energy, food, goods and labour that began in the early 1980s has reasserted itself. Markets certainly seen to think so. It should therefore be worth thinking about what happened in 2023 and why, and whether these trends can continue in 2024 and beyond.

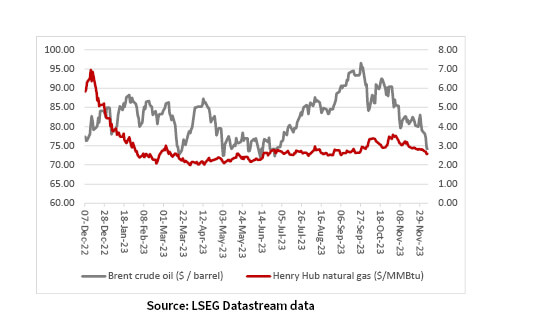

A surge in oil, and especially natural gas, prices in 2022 in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine had markets on alert. Rising energy prices were seen as bad for inflation (and even food prices, given how diesel and fertilisers are two major cost components of any farm), bad for growth (as they function as a tax on consumers’ pockets and pressure corporate profit margins) and bad for governments’ stretched finances, given the many fuel and energy subsidies that were rolled out.

“The issue now is whether oil price weakness is just about increased American supply or wider weakness in demand. If it is the latter, then the economic picture may not be so clear after all.”

Had you then told everyone there would be a war in the Middle East in 2023, the result could well have been panic, given how similar events stoked major oil price spikes in the 1970s. However, even OPEC+ production cuts have not supported hydrocarbon prices as US shale output as surged this year. The issue now is whether oil price weakness is just about increased American supply or wider weakness in demand. If it is the latter, then the economic picture may not be so clear after all.

Energy supply worries seem to have passed (for now)

Source: LSEG Datastream data

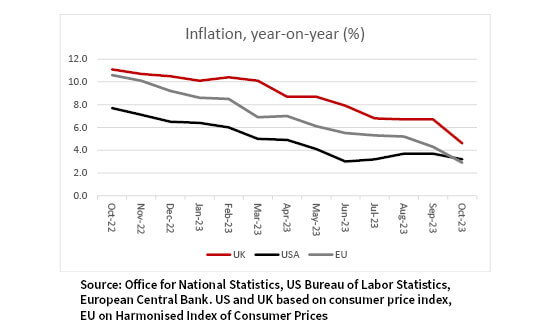

Lower oil and gas prices have helped to take the sting out of inflation and boost markets’ confidence the worst is behind us. The test now is whether we do get a repeat of the 1970s, when inflation struck in three major waves as wage and price spirals set in (and 1973’s oil price spike after the Yom Kippur war was followed by another in 1979 when the Shah of Iran fell from power).

Markets think we are past peak inflation

Source: Office for National Statistics, US Bureau of Labor Statistics, European Central Bank. US and UK based on consumer price index, EU on Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices

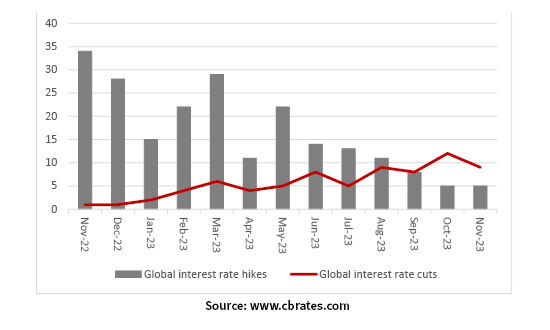

Lower energy prices and cooling inflation mean Western central banks appear to be bringing a sharp cycle of interest rate hikes to a halt, while some emerging market monetary authorities are starting to cut headline borrowing costs.

“In the US, markets are now discounting five, one-quarter point interest rate cuts in 2024, and in the UK, investors are pricing in four, with the result that borrowing costs will be 4.25% by next Christmas.”

This is sparking hopes that the longed-for pivot to lower rates and cheaper money is near. In the US, markets are now discounting five, one-quarter point interest rate cuts in 2024, and in the UK, investors are pricing in four, with the result that borrowing costs will be 4.25% by next Christmas. The Fed and Bank of England continue to protest that such talk is premature but two-year Treasury and Gilt yields are going lower (and they tend to pre-empt central banks by six to nine months).

Lower interest rates mean lower returns on cash and (usually) lower bond yields, which helps to increase the relative attractiveness of other asset classes, such as equities. But central banks must now deliver in 2024 to keep stock and bond markets happy.

Interest rate cuts are gaining momentum

Source: www.cbrates.com

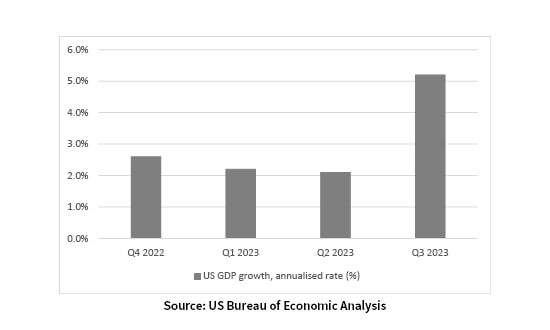

A global recession did not materialise in 2023, despite a disappointing post-COVID recovery from the world’s second biggest economy, China. The world’s largest economy, America, seemed to take up the slack, despite spring’s banking crisis, as it was buoyed by a still-confident consumer and Bidenomics, as their government spent heavily on the CHIPS and Inflation Reduction Acts. America’s latest debt ceiling breach did not stop such spending, and President Biden is unlikely to turn off the taps ahead of November’s election, but the consumer saving rate is ebbing and America’s deficit is soaring. At some stage, there remains a risk both trends provide headwinds not tailwinds, should both slow their spending.

The US economy is still powering ahead

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

“American onshoring of key technologies, to buttress supply chains and reduce reliance on China, is a major geopolitical and economic trend that will surely run (and run). The US economy is feeling the benefit and China’s is taking the pain.”

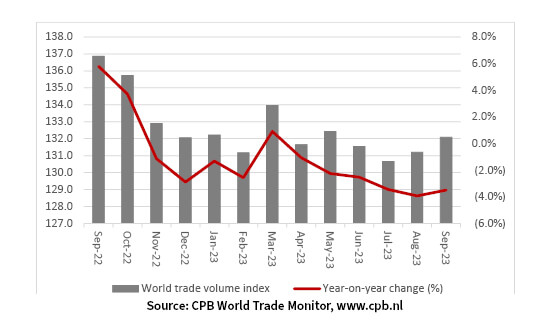

American onshoring of key technologies, to buttress supply chains and reduce reliance on China, is a major geopolitical and economic trend that will surely run (and run). The US economy is feeling the benefit and China’s is taking the pain. Tensions remain elevated and global trade flows are still subdued, which is not normally a good sign for global economic growth. Any further trade and tariff tiffs in 2024 may not be helpful as the global outlook may be more delicate than it looks.

Global trade flows remain sluggish at best

Source: CPB World Trade Monitor, www.cpb.nl

Next week’s column will look at what could be the key macroeconomic trends in 2024 and how they in turn could shape the performance of advisers’ and clients’ portfolios.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and some investments need to be held for the long term.

This area of the website is intended for financial advisers and other financial professionals only. If you are a customer of AJ Bell Investcentre, please click ‘Go to the customer area’ below.

We will remember your preference, so you should only be asked to select the appropriate website once per device.