The FTSE 100’s (thus far) brief flirtation with the 8,000 level is attracting a lot of attention, and the very fact that it is doing so may be a sign that UK equities are still the subject of much scepticism, as the tone of the mainstream coverage seems to be one of pleasant surprise.

“Bears will scowl and argue that capital is best allocated elsewhere, on the grounds that the FTSE 100 is a twenty-first century index with a distinctly twentieth-century mix to it.”

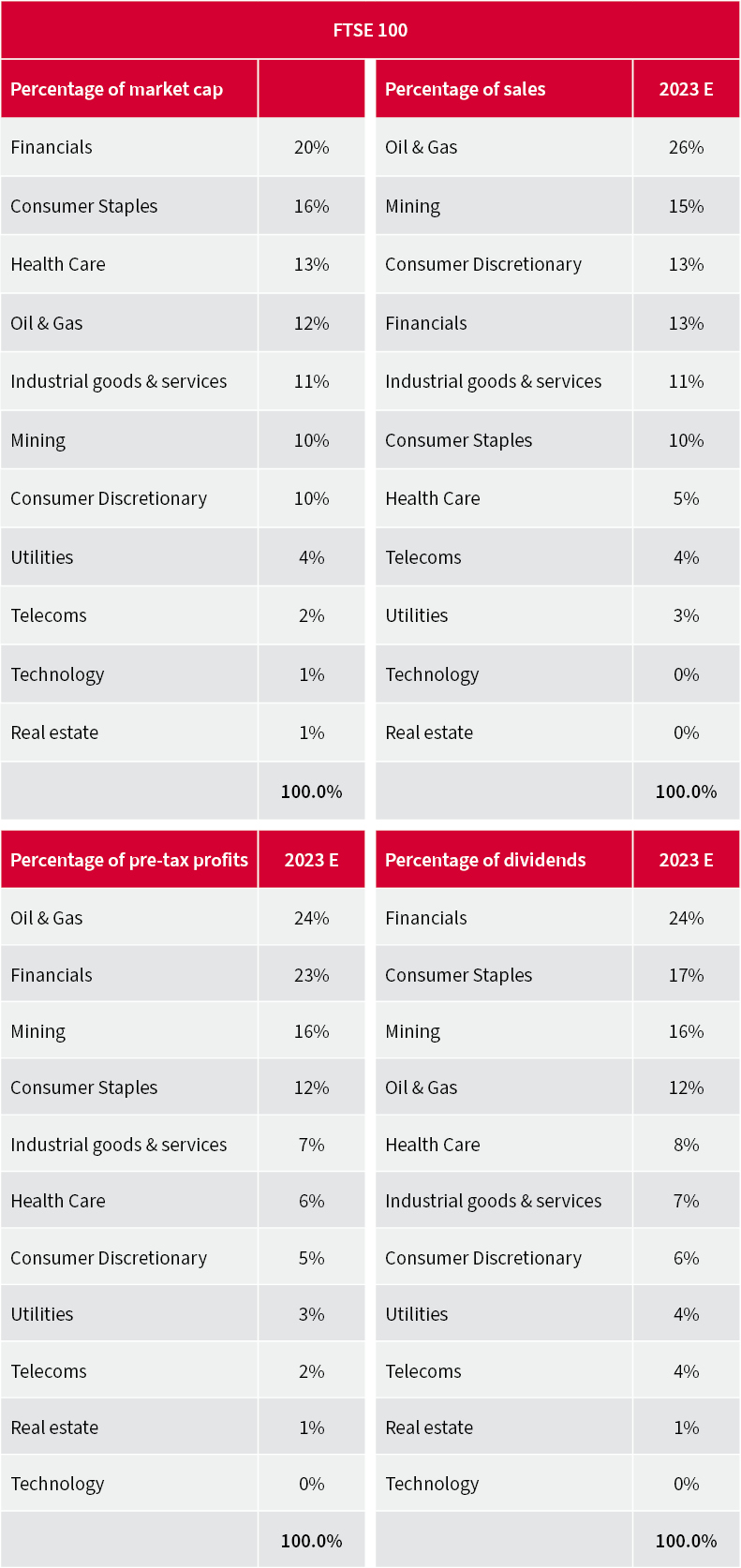

Bulls will smile at this and point to fund management legend Sir John Templeton’s axiom that: “Bull markets are born on pessimism, grow on scepticism, mature on optimism and die on euphoria.” Bears will scowl and argue that capital is best allocated elsewhere, on the grounds that the FTSE 100 is a twenty-first century index with a distinctly twentieth-century mix to it, given its reliance upon mining, oils, banks, financials and consumer staples and limited exposure to technology.

To try and ascertain where the UK market goes from there (and whether 9,000 and 10,000 are easy next steps or major mountains to climb), investors need to address four questions:

“Using the FTSE 100 index as a proxy for the wider market, UK equities were, frankly, overpriced in 1999 as technology, media and telecom stocks sluiced into the index, only to then fail to meet overhyped expectations and then sluice straight back out again.”

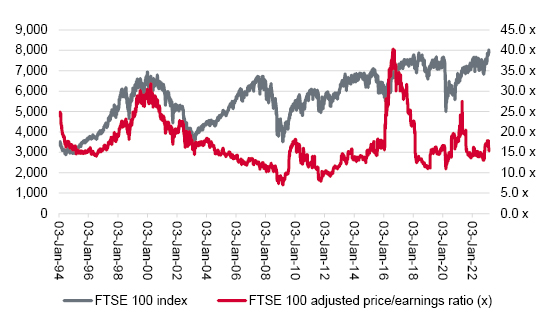

One major reason why the FTSE 100 has struggled to make major progress since the start of the millennium is valuation, which is the ultimate arbiter of investment return. Using the index as a proxy for the wider market, UK equities were, frankly, overpriced in 1999 as technology, media and telecom stocks sluiced into the index, only to then fail to meet overhyped expectations and then sluice straight back out again.

The FTSE 100 failed to justify the lofty valuations paid at the 1999

Source: Refinitiv data

Their far-from-graceful exit then left the FTSE 100 underweight in technology stocks and long-duration assets when they came back into fashion after the Great Financial Crisis. A decade’s worth of low growth, low inflation and low interest rates placed a premium on dependable, sustained growth and yield and the FTSE 100 found it hard to offer either, unlike tech and biotech stocks on one hand and Government bonds on the other.

Instead, the UK benchmark was packed with short-duration, cyclical assets such as banks, oils and miners, with a little welcome stodge from consumer staples and pharmaceuticals on top.

“The bulk of the FTSE 100’s earnings and dividends come from cyclical, ‘value’ sectors and that may be no bad thing at a time of rising inflation, higher nominal growth and rising interest rates.”

Those facets were a handicap in the 2010s, but they have become more of an asset in the 2020s. The bulk of the FTSE 100’s earnings and dividends come from cyclical, ‘value’ sectors and that may be no bad thing at a time of rising inflation, higher nominal growth and rising interest rates. A higher cost of capital may also place a premium on the sort of cashflow and financial solidity that well-established megacaps can provide and early-stage growth stocks cannot.

FTSE 100’s fortunes lie with oils, miners and banks in particular

Source: Marketscreener, consensus analysts’ forecasts

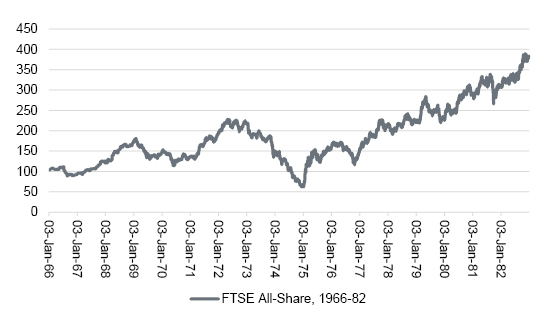

Yet there are clearly still risks. A long and deep recession could puncture oil and metals prices, increase banks’ bad loan provisions and drag interest rates lower once more. A fierce and sustained inflationary outbreak might not be helpful either. The FTSE All-Share suffered terribly in the early 1970s after the Barber crack-up boom and an oil price shock saw inflation reach double digits. The forward price/earnings ratio of the All-Share bottomed in the low single-digits and anyone who put money into UK equities in 1966 had to dutifully wait until 1982 to get their money back in real, inflation-adjusted terms.

Yet even then, UK stocks offered better protection against inflation than either cash or bonds and the All-Share rallied furiously from its 1974 nadir.

Again, bulls will argue that this is where the opportunity may now lie, if indeed a 40-year era of cheap money, cheap energy, cheap labour and cheap goods is coming to an end, as the FTSE 100’s exposure to real assets, in the form of commodities, real estate and property, could offer some hedge against the ravages of inflation relative to paper ones like cash or bonds.

FTSE All-Share offered a rollercoaster ride in the inflationary 1970s

Source: Refinitiv data

“The FTSE 100 is not as cheap as the All-Share was in 1974 but it trades at hefty discounts to its American and European peers on around 11 times forward earnings and a 4% dividend yield for 2023, according to consensus analysts’ forecasts.”

The FTSE 100 is not as cheap as the All-Share was in 1974 but it trades at hefty discounts to its American and European peers on around 11 times forward earnings and a 4% dividend yield for 2023, according to consensus analysts’ forecasts. Add a currency which is yet to recapture the ground lost in the wake of the Brexit vote to a period of sustained underperformance and UK equities could be cheap, as around dozen takeover bids from trade or financial buyers for FTSE 100 members since 2016 may also attest.

Granted, those forecasts could be optimistic and the weighting toward oils, miners and banks lends the index a distinct air of unpredictability. But the lowly multiples attributed to those forecasts, and the meaty yield that investors are demanding in compensation for the perceived dangers, suggests faith in them is not high and that at least a degree of bad news is already factored into share prices and index levels.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and some investments need to be held for the long term.

This area of the website is intended for financial advisers and other financial professionals only. If you are a customer of AJ Bell Investcentre, please click ‘Go to the customer area’ below.

We will remember your preference, so you should only be asked to select the appropriate website once per device.