Xiang Guangda, founder of Chinese nickel firm Tsingshan, joins an infamous list of firms and traders who have had their trousers pulled right down when trading commodities. But neither the humbling experience nor its scale – a reported $8 billion paper loss – are as rare as advisers and clients might think.

The main lesson to draw from this when it comes to commodities trading is therefore “don’t try this at home,” especially if you are using leverage (or trading margin using borrowed money) to do it. By all means, take a considered long-term view on commodities as part of a diversified portfolio, if it fits with your overall strategy, time horizon, target returns and appetite. Go all in on one commodity and trade it like a dervish – definitely not.

“The main question that this accident begs is just how far can commodity prices go? The London Metal Exchange had to suspend trading in nickel, such was the chaos, and once business began again the metal quickly retreated.”

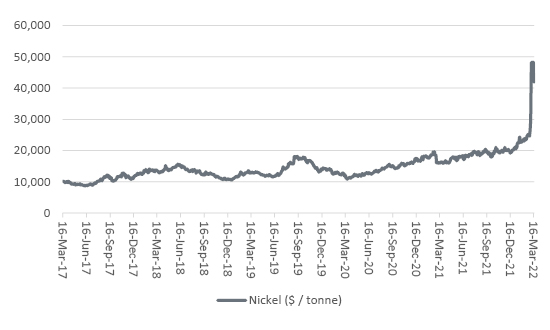

The main question that this accident begs is just how far can commodity prices go? The London Metal Exchange had to suspend trading in nickel, such was the chaos, and once business began again the metal quickly retreated. This is not the sort of action that you see at market bottoms when sentiment is washed out.

Nickel has been a very volatile market

Source: Refinitiv data

That in turn begs the question of what could happen to commodity-related stocks? They represent almost a fifth of the market capitalisation of the FTSE 100, so further gains or losses could have an impact on the headline index – something which investors who own trackers of exchange-traded funds (ETFs) should consider, even if they have no interest in researching or buying individual stocks themselves.

“The net result was an $8 billion loss, on paper anyway, and entry into a far-from exclusive club of big commodity price losers.”

Xiang Guangda’s troubles stem from a short position on nickel. This was based on the premise the metal would fall in value, but instead it rose sharply as traders and industrial buyers fretted about the potential loss of Russian supply, and he then had to close out his position, buying more metal and creating a self-fulfilling (and in Xiang’s case self-defeating) upward price spiral. The net result was an $8 billion loss, on paper anyway, and entry into a far-from exclusive club of big commodity price losers which includes:

“The best cure for high prices is high prices as they prompt a search for other options or force users to consume less.”

The Tsingshan losses are the first major accident in the commodities market for a while (and in inflation-adjusted terms the Bunker Hunts came a far bigger cropper) but they do beg the question of whether they are sounding a bell for a market top in the price of not just nickel, but raw materials across the board after their recent surge. The best cure for high prices is high prices as they prompt a search for other options or force users to consume less. Unlikely as it may seem right now, any sort of ceasefire or peace deal in Ukraine could also ease a lot of fears over supply from Russia, which is a top-five global provider of palladium, diamond, gas, oil, platinum, aluminium, potash, nickel, titanium and steel.

However, the conflict is not the only story when it comes to commodities (and nor are commodities the only story when it comes to the conflict, given the human suffering involved). Neither miners nor oil explorers have invested heavily for some time in new capacity, owing to the combination of weak commodity prices in the middle of the last decade, the need to pay down debt after an acquisition spree, calls for higher cash returns from investors and pressure from environmental campaigners (and the wider public).

“If demand remains strong, either from industrial buyers as the global ticks along, or financial ones if they feel the need to seek a haven from inflation, then raw material prices could yet move higher over time.”

If demand remains strong, either from industrial buyers as the global ticks along, or financial ones if they feel the need to seek a haven from inflation, then raw material prices could yet move higher over time.

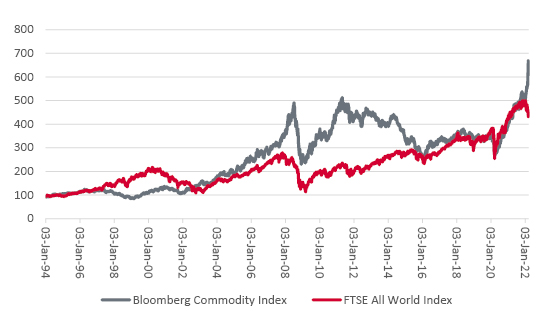

Some of the potential upside does look priced in, since the Bloomberg Commodity Index is once more handily outperforming the FTSE All-World Equity Index, just as it did during 2000-2010 period when central banks had to slash interest rates in two cycles in the face of two economic and stock market busts – maybe the policy response to the pandemic will produce another upswing.

Commodities are once more outperforming equities

Source: Refinitiv data

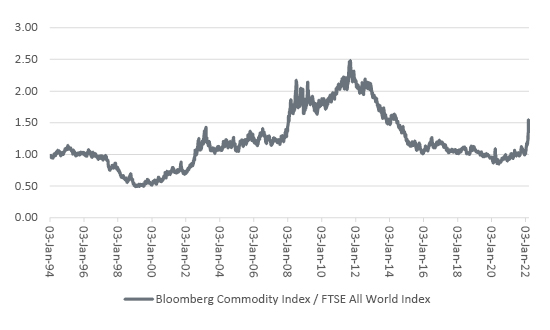

“Analysis of the Bloomberg benchmark against the FTSE All World on a relative basis shows a slightly different picture. If commodity prices really go into orbit, then this suggests ‘real stuff’ could outperform ‘paper assets’ for a good while and by a good degree yet, especially if inflation or stagflation are the ultimate economic outcome.”

But analysis of the Bloomberg benchmark against the FTSE All World on a relative basis shows a slightly different picture. If commodity prices really go into orbit, then this suggests ‘real stuff’ could outperform ‘paper assets’ for a good while and by a good degree yet, especially if inflation or stagflation are the ultimate economic outcome. Commodities outperformed equities much more strongly and for much longer in the 2000s than they have thus far this time around.

Commodities not outperformed equities to the degree seen in the early 2000s

Source: Refinitiv data

Equally a recession would in all likelihood be bad news for many commodities, especially industrial metals, although precious metals could yet shine under those circumstances, depending upon the policy response from governments and central banks.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and some investments need to be held for the long term

This area of the website is intended for financial advisers and other financial professionals only. If you are a customer of AJ Bell Investcentre, please click ‘Go to the customer area’ below.

We will remember your preference, so you should only be asked to select the appropriate website once per device.