In the film Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Arthur, King of the Britons, comes across two peasants, Dennis and his mud-shovelling partner. A polite request for directions leads to a testy exchange between the ruler and his subjects which concludes with Arthur losing his temper and the poverty-stricken pair claiming they are being unfairly abused amid cries of “Come and see the violence inherent in the system” and “Help! Help! I’m being repressed!”

“The concept of repression in a financial context is one with which advisers and clients are becoming more familiar, whether they realise it or not.”

Very funny as that scene is, the concept of repression in a financial context is one with which advisers and clients are becoming more familiar, whether they realise it or not. Trends that were in place before the pandemic may now be accelerating as governments rack up ever-higher deficits and central banks cut interest rate to new lows and ramp up quantitative easing (QE) to fresh peaks in their understandable desire to try and do something to help.

Arthur, King of the Britons, may have given Dennis a clip around the ear when he did not get the information he wanted but it could be argued that advisers and clients need to be aware of, and prepared for, the danger of a sharp jab to the wallet.

From the narrow perspective of the UK, the last numbers with which we can work are those presented in the Budget of March 2020, although the world already looks like a very different place.

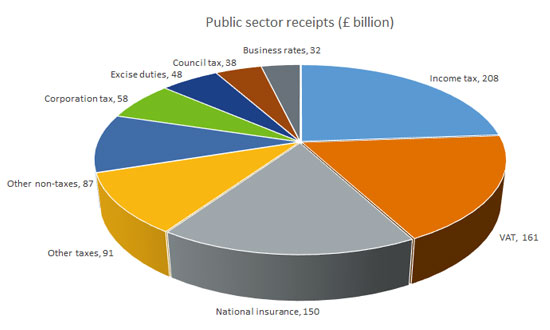

The Budget forecast annual central Government expenditure of £928 billion, with £285 billion going on what Chancellor Rishi Sunak termed ‘social protection’ (COVID-19 costs), £178 billion on the NHS and £116 billion on education.

Income was forecast to be £873 billion, with the bulk of that coming from Income Tax (£208 billion), VAT (£161 billion) and National Insurance (£150 billion), followed by Corporation Tax (£58 billion) and Excise Duty (£48 billion).

How the Government raises money and where it goes

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility, HM Treasury, March 2020 Budget

The pandemic has wrecked Mr Sunak’s best-laid plans, since outgoings have exceeded receipts by £200 billion in the first six months of the year alone.

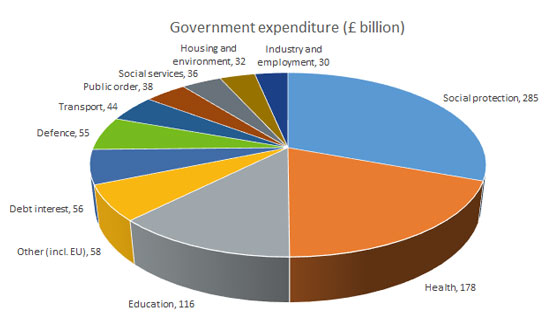

The Government fills any revenue shortfall with borrowing and each annual deficit adds to the aggregate public debt, which now exceeds £2 trillion for the first time. The UK then funds this by selling treasury bills and gilts to institutional investors such as life insurance companies or overseas buyers, as well as banks and building societies, which use the interest on those debt instruments to match or fund their own future liabilities, such as interest or pension payments or insurance claims. The UK also sells National Savings & Insurance products to private individuals.

How the Government funds its borrowing

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility

“Usually, higher borrowing would lead to higher interest costs as lenders (gilt buyers) seek greater compensation to reflect the increased risk reflected by the growing debt pile – even if the UK has not failed to pay interest on its debt since 1672 and the Stop of Exchequer under King Charles II.”

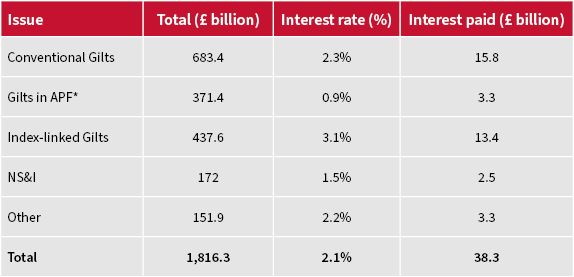

A new wrinkle from the past decade is that the Government issues gilts (debt) and the Bank of England then buys it, under its QE programme, to both mop up supply and keep the coupon – or interest rate – on the gilts as low as it can, to help the Government fund its spending. Usually, higher borrowing would lead to higher interest costs as lenders (gilt buyers) seek greater compensation to reflect the increased risk reflected by the growing debt pile – even if the UK has not failed to pay interest on its debt since 1672 and the Stop of Exchequer under King Charles II.

In November, the Bank of England added £150 billion to QE, to take the total to £875 billion, getting on for half of the gilts in issue. That is helping to anchor the benchmark 10-year gilt yield at 0.35%, as is the headline base interest rate, which is set at an all-time low of 0.1%.

How monetary policy can help Government’s fiscal policy

Source: Refinitiv data

That helps the Government service the debt but not necessarily to repay or reduce total borrowing, where there are three options:

“Harvard Professor Carmen Reinhart further developed the concept of ‘financial repression’ in a National Bureau of Economic Research paper back in 2010, when she outlined the four mechanisms governments could use to reduce their debts by sequestering cash that would flee elsewhere if it had the chance.”

Harvard Professor Carmen Reinhart further developed this concept in a National Bureau of Economic Research paper back in 2010, when she outlined the four mechanisms governments could use to reduce their debts by sequestering cash that would flee elsewhere if it had the chance:

Step one is already being taken and step two is arguably on its way, as the Government gets banks to issue state-backed loans to companies to help them through the pandemic. Step three would be next if financial firms are leaned upon to buy gilts (with central banks possibly also issuing their own digital currencies backed by assets purchased through QE, or even with those assets being made legal tender). The Bank of England could also just directly fund major infrastructure projects to try and get the economy going via ‘The People’s QE’.

There seems to be little political or public appetite for tax increases and it does not yet feel as it GDP growth is about to rip higher and help the Government inflate away its debts – although if it does, then ‘real’ assets such as commodities and property may come back into vogue over ‘paper’ ones, such as gilts and the Government’s promises to pay its interest, which will offer little more than return-free risk, given the nugatory yields on offer.

Nor is there any sign of financial market revolt, but history suggests there is always a tipping point somewhere, when lenders (bond buyers) refuse to fund Government debt, or at least demand very high yields in return for doing so. That is where financial repression would come in, to stem the tide of bond selling and oblige banks or financial intermediaries to own gilts whether they are offering positive returns or not.

It might offer gilts and bonds some support, but it would do nothing for banking or insurance stocks, for example, and the degree to which equities are affected would depend on the degree of repression, the state of the economy and whether capital controls come too – if so, investing overseas and finding money trapped there would hardly be an attractive option.

Rapid growth is therefore the best of the three scenarios for equities, so advisers and clients may need to start crossing their fingers. But then, hope is not a strategy, which may be why assets such as gold and Bitcoin are performing relatively well as advisers and clients seek a bolthole from the threat of ‘financial repression’.

This area of the website is intended for financial advisers and other financial professionals only. If you are a customer of AJ Bell Investcentre, please click ‘Go to the customer area’ below.

We will remember your preference, so you should only be asked to select the appropriate website once per device.