Calls from both the Bank of England’s Governor, Andrew Bailey, and its Chief Economist, Huw Pill, for wage restraint do not sit easily alongside the current headline inflation figures. Nor does Unilever’s statement (10 Feb) that it raised prices by 4.9% in the fourth quarter of last year and has planned further hikes in 2022, thanks to expected input cost inflation of 3% to 4%.

“Calls from both the Bank of England’s Governor, Andrew Bailey, and its Chief Economist, Huw Pill, for wage restraint do not sit easily alongside the current headline inflation figures. Nor does Unilever’s statement (10 Feb) that it raised prices by 4.9% in the fourth quarter of last year.”

A few small caps, notably own-brand cleaning products specialist McBride, loo roll maker Accrol and retailer Joules, have dished out profit warnings as they proved unable to raise prices far or fast enough to compensate for rising costs.

But Unilever is the biggest so far, as it forecast a drop in profit margins of some 1.4 to 2.4 percentage points in 2022, down to 16% to 17%. Even though not all of this is down to higher raw material, freight and packaging costs, as the food-to-personal-care giant continues to invest heavily in product development and marketing, it does beg the question of who is able to defend product margins in an inflationary environment if Unilever cannot? After all, it can call upon the power of brands such as Marmite, Hellmans, Dove and Magnum.

Such company-specific issues will be beyond the remit of advisers on behalf of their clients, but both need to find the right fund manager to help them navigate these issues because portfolios with substantial equity exposure are now confronted by key questions:

“A classic inflationary cycle runs from commodity prices to factory gate (or producer) prices to consumer prices and finally through to wages.”

Although politicians (and consumers) understandably like the idea of a “high wage economy” central bankers seem less keen. A classic inflationary cycle runs from commodity prices to factory gate (or producer) prices to consumer prices and finally through to wages. If pay starts to rise, and consumers become accustomed to paying higher prices and believe they will do so again in the future, then inflation expectations start to become untethered, the circle is completed and rising demand and prices for finished goods trickles back to raw materials to feed the next leg of the cycle.

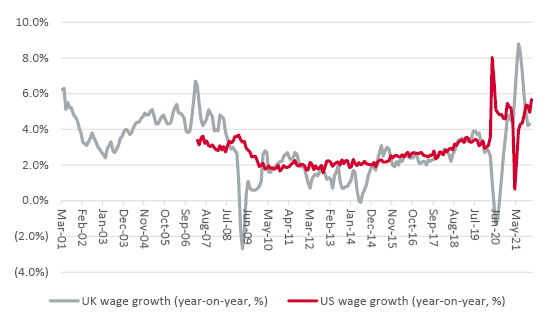

Wage growth is cooling a little on both sides of the Atlantic, but the readings are still high by the standards of the (admittedly relative short) datasets that we have. In the UK, total pay (including bonuses) rose by 4.3% year-on-year in the three months to November, and US workers’ average hourly pay rose 5.7% year-on-year in January.

Wage growth remains robust in the UK and USA

Source: Office for National Statistics, US Bureau for Labor Statistics, FRED – St. Louis Federal Reserve database

Low unemployment rates and high numbers of job vacancies relative to the numbers of those without work would suggest labour may just have the whip hand in any pay negotiations. Trades unionists and workers may be happy about that for political, philosophical and economic reasons as there can be little doubt that capital has had its wicked way with labour for much of the past four decades, and beyond.

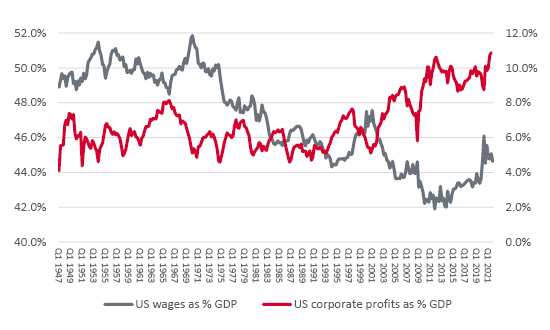

“Since 1947, Americans’ pay has fallen by more than four percentage points as a portion of GDP. American corporate profits have increased by around six percentage points over the same time frame.”

Since 1947, Americans’ pay has fallen by more than four percentage points as a portion of GDP. American corporate profits have increased by around six percentage points over the same time frame.

US corporate profits have benefited from sustained pressure on wages

Source: FRED – St. Louis Federal Reserve database

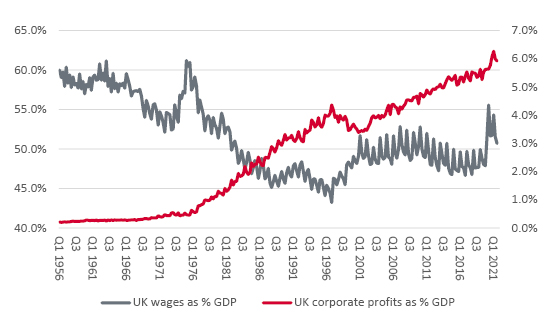

A similar trend can be seen in the UK, where the data goes back to 1955. Since then, labour’s take-home slice of the economy has dropped by almost ten percentage points, while corporations have increased theirs by the thick end of six points.

UK corporations have also put the squeeze on workers’ remuneration

Source: Office for National Statistics

Advisers and clients could therefore be forgiven for wondering what may happen next. After all, corporate profits stand at, or close to, a record high as a percentage of GDP in both the USA and UK. Any margin pressure could therefore restrict profit growth (and that is before UK-based firms face a jump in corporation tax to 25% from 19% from April 2023). And the combination of higher interest rates and slower profit growth is not an ideal one, especially in the US equity market, where valuations are at or near all-time peaks, based on market-cap-to-GDP and the Shiller cyclically adjusted price earnings (CAPE) ratio.

Yet all may not be lost for three reasons. Higher pay could help consumers keep spending. Companies report sales and profits in nominal, not real, inflation-adjusted terms. Sales up, costs up can still mean profits up, which is why equities are seen as offering a better hedge against inflation than say bonds.

“Granted, some companies and industries may be better suited to coping with inflation than others … Luckily, the FTSE 100 has quite a few of those.”

Granted, some companies and industries may be better suited to coping with inflation than others. Areas where demand is relatively price inelastic, or insensitive, are one – they include oil and tobacco. Industries where demand growth outstrips supply growth (and it takes time to create fresh supply) are another – and that could include mining, especially as central banks cannot print copper, gold or cobalt. And consumer staples or luxury goods companies with brands can be better placed than most to raise prices thanks to the customer loyalty and pricing power they confer.

Luckily, the FTSE 100 has quite a few of those.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and some investments need to be held for the long term.

This area of the website is intended for financial advisers and other financial professionals only. If you are a customer of AJ Bell Investcentre, please click ‘Go to the customer area’ below.

We will remember your preference, so you should only be asked to select the appropriate website once per device.