Well, that didn’t take long. The Fed began to pump less Quantitative Easing (QE) into the financial system in November and the stock market’s wheels have already started to wobble after barely two months of less ‘cheap’ money, let alone any move to withdraw it.

Advisers and clients can therefore be forgiven for starting to ask themselves how much the US Federal Reserve can do to tighten monetary policy, before it either puts the brakes on the economy, breaks the stock market, or both. In a worst case, the answer might be not very much at all.

“Recent precedents for tighter monetary policy (or even simply, less loose, less accommodative policy) are enough to give advisers and clients pause for thought.”

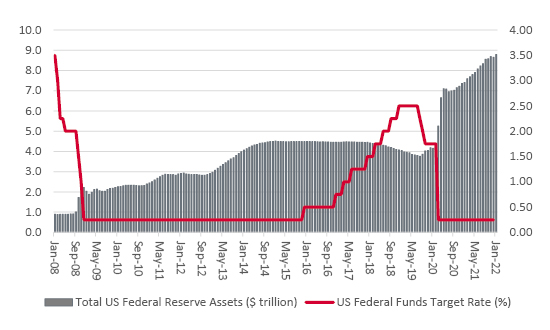

Recent precedents for tighter monetary policy (or even simply, less loose, less accommodative policy) are enough to give advisers and clients pause for thought:

The Fed’s last two efforts to tighten policy did not get far

Source: FRED - St. Louis Federal Reserve database, US Federal Reserve

Financial markets have not forgotten this and have become edgy. In theory, that should not be the concern of the US Federal Reserve, or indeed any central bank. Their job is to keep inflation on the straight and narrow, to ensure it does not destroy wealth and prosperity or imbalance the economy.

But a decade and more of zero interest rates and QE – unintentionally or intentionally (judging by a string of speeches from former Fed chair Ben S. Bernanke dating back to at least 2003) – have persuaded or forced advisers and clients to take ever-increasing amounts of risk to get a return on their money.

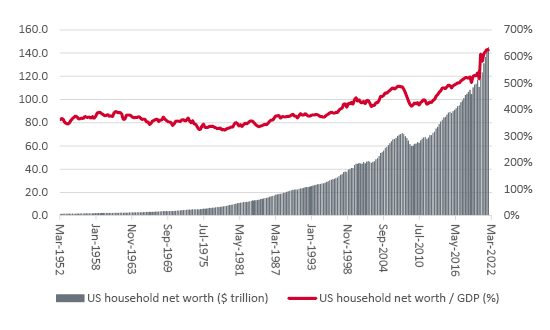

“US household wealth stands at a record high relative to GDP, thanks to booming stock and house prices. If that goes into reverse, the hit to confidence, and consumers ability and willingness to consume, could be considerable.”

Central banks are presumably concerned that having tried to create a wealth effect by stoking asset prices, the opposite effect could now kick in. US household wealth stands at a record high relative to GDP, thanks to booming stock and house prices. If that goes into reverse, the hit to confidence, and consumers ability and willingness to consume, could be considerable.

US household net worth stands are a record high as a percentage of GDP

Source: US Federal Reserve, FRED - St. Louis Federal Reserve database, M&G Bond Vigilantes

Central banks may therefore be stuck between a rock and a hard place. They will want to control inflation on one side, but their ability to jack up interest rates may be constrained by record debts and concerns about the economy, employment (and financial markets’ stability) on the other.

Advisers and clients will have choices to make too.

“If the low-growth, low-inflation, low-rates of the last decade are replaced by higher inflation, higher nominal growth and higher rates it would be logical to expect the outperformers of the last decade (long-duration assets, bonds, tech and growth equities) to struggle, and the underperformers of the last decade (short-duration assets, commodities and cyclical, value equities) to have a chance of a return to favour.”

If the low-growth, low-inflation, low-rates of the last decade are replaced by higher inflation, higher nominal growth and higher rates it would be logical to expect the outperformers of the last decade (long-duration assets, bonds, tech and growth equities) to struggle, and the underperformers of the last decade (short-duration assets, commodities and cyclical, value equities) to have a chance of a return to favour.

A change in market leadership does not necessarily signify a collapse, even if it raises the stakes, but more volatility seems likely unless oil and gas prices start to retreat and cut central bankers, politicians and the public a break.

If forced to choose, this column reckons they will take their chances with inflation and even cut rates and resume QE if the going gets tough.

That could bring fresh challenges of its own. History students know that we have been here before. Jens O. Parsson wrote Dying of Money: Lessons of the Great German and American Inflations in 1974, when US inflation was running rampant thanks to President Nixon’s demolition of Bretton Woods and withdrawal of the dollar’s link to gold, rampant US spending on welfare and Vietnam, and the 1973 oil price shock. He drew parallels between the German experience of the 1920s with that of the US in the 1960s and 1970s, even if the Volcker-led Federal Reserve took upon itself the job of reining in inflation. It did this, albeit at the cost of recessions in 1980 and 1981-82 during President Reagan’s first term.

No-one is expecting a 1920s Weimar-style collapse but the US in the 1970s was not much fun for advisers and clients either. Advisers and clients may need to consider Parsson’s conclusion and, if they consider it relevant, where we may be in the inflationary cycle today and the difficult decisions that central banks and governments may need to take as a result. The author (who was using a pen name) concluded:

“Everyone loves an early inflation. The effects at the beginning of an inflation are all good. There is steepened money expansion, rising government spending, increased budget deficits, booming stock markets and spectacular general prosperity, all in the midst of temporarily stable prices. Everyone benefits and no-one pays. That is the early part of the cycle. In the later inflation, on the other hand, the effects are all bad. The government may steadily increase the money inflation in order to stave off later effects but the later effects patiently wait. In the terminal inflation, there is faltering prosperity, weakness of money, falling stock markets, rising taxes, still larger government deficits and still roaring money expansion, now accompanied by soaring prices and ineffectiveness of all traditional remedies. Everyone pays and no-one benefits. That is the cycle of every inflation.”

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and some investments need to be held for the long term.

This area of the website is intended for financial advisers and other financial professionals only. If you are a customer of AJ Bell Investcentre, please click ‘Go to the customer area’ below.

We will remember your preference, so you should only be asked to select the appropriate website once per device.